This post may contain affiliate links.

I’d like to send a five-star review into cyber space in favor of Alan Watt’s The 90-Day Novel. For nearly four years this has been my go-to book for organizing my writing scraps into stories.

If you don’t want to get bogged down “reading about writing”; but feel you need help starting and staying on track with your manuscript, this is the book for you.

Most daily lessons are around two pages and provide plenty of inspiration to get you typing.

I’ve worked through The 90-Day Novel seven times and now feel torn between leaving a straightforward, practical review here – or sharing the gut-honest truth of how my heart had been absolutely crushed and pulverized just prior to purchasing this book – and how much it helped me – not just with my manuscripts.

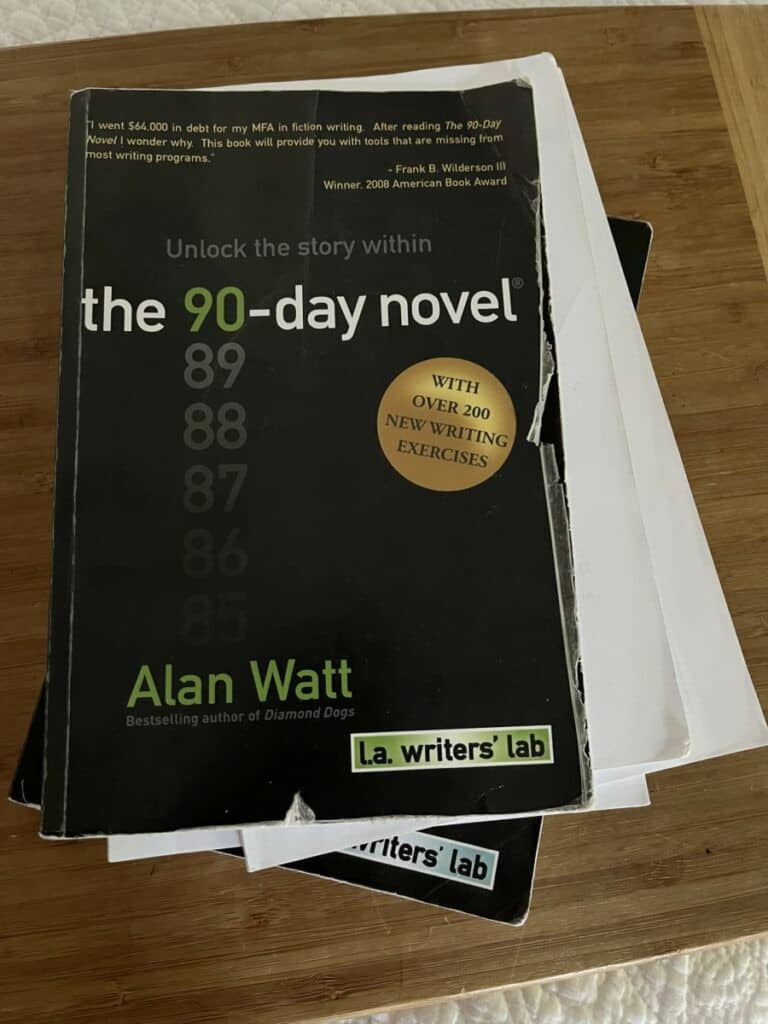

Judge This Book By It’s Cover

A picture is worth a thousand words. The tattered cover of my copy of The 90-Day Novel says more than my wordy review ever could…

Here’s a video review, if you’d like a closer look:

This book did instruct me in how to write a novel; but it also showed me how to sift through the fragments of my broken dreams and help me see the beautiful mosaic that my suffering could become.

copy of The 90-Day Novel

fell apart, my story began to come together in a series,

instead of just one book.

The Backstory on Why I Bought The 90-Day Novel

I guess I should just go ahead and give you a glimpse into my story to help explain why what started out as an attempt at a novel became a series of books, and also helped with a slow healing of my heart.

I had planned to go to Thailand in February of 2019 to assist refugees displaced by civil war. Instead, just as I was going to buy my tickets, I found out my aunt had cancer, and my uncle, Danny, was having severe health problems, which turned out to be a glioblastoma brain tumor.

Within a day, I left Texas and moved to Wabash, Indiana – a town that I had always felt was most like home, though I had never actually lived there.

For seven months, I watched Danny – feeling like a thousand strings were attached to my stomach, tearing at the nerves. We sat in silence, hearing nothing but the clock tick, the attic fan, the ice maker, the birds and the dogs.

I could hardly stand it.

Danny had always been a story teller.

I usually had little to say; but loved to listen and watch his eyes light up.

He said so little while he was sick, and I couldn’t think of much to fill in the silence.

I Was Raised in a Culture of Story Tellers, Mentally Taking Notes

Danny had talked about the nursing home where he’d worked after Vietnam, recounting how one resident had taken the notion to gather everybody else’s false teeth for a good cleaning. When the staff found all those dentures soaking together, they had quite a time discerning which set to redistribute to which patient.

For a long time, I’d said, “Somebody ought to write a book about that place.” I wondered who would.

In 2013, my grandma died. She was nearly 102 years old; but I didn’t feel ready to say goodbye. I wanted to know more about her life. There was so much I’d missed.

Her first gift to her mother-in-law was offensive. My grandma hadn’t realized it might hurt the woman’s feelings to open a package with two gloves when she only had one hand, having lost the other in a factory accident as a teenager. It was a new concept to me to realize that even old ladies have lived through embarrassing moments.

From her I’d learned about The Great Depression and been told about how she and her sisters would sleep three to a bed, sometimes waking up with frost on the walls.

We’d laughed about how her younger sister, Frances, was asked by a neighbor where she slept in that little house with six other siblings, and responded, “I sleep on the ironing board!” I don’t think that was really the case; but Frances had all sorts of quotable statements, and I kept wanting to record them.

I’m so tempted to tell them here; but I have to remind myself that this is a

book review and a blogpost, not a biography…

Sometimes I have a hard time staying on topic – another reason I benefited from Al Watt’s book…

The Story I Most Want to Tell is About That Barn

I do just have to say that my whole story stems from a certain barn that sat out in the country.

That barn was built in 1861, the year our nation went to war against itself.

It was my “safe-space” when I was a kid – and ironically, the place I did all sorts of dangerous things.

That barn was the reason I wanted to be a successful writer – I wanted to save it and bring it back to life when it was falling apart.

In 2014 it broke my heart to watch it be sold at auction and know I had no money to make a bid.

The love of money can make a mess of relationships, and the sale of that farm caused quite a stir. I felt bad for Danny and remember following him around during that season, as I so often did, saying, “Somebody ought to write a story about this. I think it ought to be called, ‘The Inheritance’.” I wondered who would.

In the midst of my heartbreak that barn connected my heart with a ninety-four-year-old lady, named Jean Wilson, who had also played in that barn as a girl and loved it dearly.

Her unexpected generosity, in giving me an aged photograph of the barn, from her own kitchen wall, was a stark contrast to the selfish greed I was watching unfold among some of my relatives. I’d wanted a picture from my grandma’s; but was told I could buy it at the sale, because it might bring a lot of money at the auction. Instead I was offered “a nice basket” from someone who had just pocket a gold cross and claimed dibs on the washer and dryer.

The day of the sale, I went to Jean. She was a comfort in my sorrow. I was glad the barn went to a nice family; but they couldn’t afford to fix it either, and the structure was becoming unsafe. It would have taken a million dollars to save it.

I couldn’t tell if it was the best news, or the worst, when my mom told me that someone was going to save the barn. The catch was that it would be taken apart and moved to Colorado to be used as a wedding venue.

I couldn’t believe it. Of all the states, why did it have to be there? I couldn’t say why this bothered me so much. It was too embarrassing to admit I was still struggling with flashbacks from eighteen years before on that icy stretch of I-70 – and all that followed. There were fears that no one knew. Details I didn’t think I was allowed to disclose. Everyone else had moved on. Why couldn’t I?

I felt like I was watching my childhood be dismantled the day I stood with Danny, watching that barn being taken down piece by piece.

And I felt like a failure. I hadn’t been able to save it. My attempts at being an author had totally flopped.

Al Watt’s The 90-Day Novel was like finally having someone saying,

“Keep Going. You Can Finish This”,

instead of the familiar echo of my own voice telling me I was just wasting my time to try to write.

Danny stood there beneath the barn’s towering posts. It was the first time I realized that he had become an old man. I wondered how I would endure it, if someday he was taken, too.

We’d almost lost him so many times. It had only been a few years since he was nearly struck by a car and risked his life to pull the driver from her burning vehicle. I could still remember the flames lapping at the new-to-him semi we’d been admiring.

The scene took me back to Colorado; but I didn’t say that. I’d already been rebuked for telling someone not to go too fast in the fog. She didn’t know what the white around us was reminding me of.

She nodded toward the helicopter and said, “Poor Danny, this has got to be bringing Vietnam back to him.”

I didn’t tell him about the scenes coming back to my mind; but it was a comfort to know that someone knew those same feelings – of helpless fear from the past entering in and taking over the present.

He didn’t die the night of the accident; but after the barn was dismantled, he only lived a little over a year.

I thought that tumor in his brain might kill us both.

In the tearing hurt of it all, I was thankful for Jean’s love. For a few years she’d told me of watching people she loved suffer with cancer, and learning to let go of them. I was depending on her being there to hold my hand and be a comfort, as I prepared for Danny to slip away.

Unexpectedly, Jean went first. I had no clue more than one heartbreak could come before I was finished with another. She was just shy of celebrating a century of life. It felt too soon to say goodbye.

The 90-Day Novel Became a Means for Recording Multiple Heartbreaks and Remembering the Humorous Parts, Too

I kept bracing myself against the coming impact of losing Danny. Once one of the strongest men I knew, he no longer had the strength to even scratch his own face, so I had to do it for him.

On another morning that I thought might be his last, I got a text saying my great aunt, Ruth, who reminded me so much of my grandma was actively dying.

I should have seen that coming; but have never been good at multi-tasking, and hadn’t realized she could be taken, too. It was like cringing, waiting to be hit from one side, only to be slammed in the jaw from the other.

I tried all day to get to Ruth to say goodbye; but there was one calamity after another that kept me back. When I finally entered her room, it was dark.

As with almost any place where I show up, I felt like maybe I shouldn’t be there. Habitually wanting to apologize for my existence, I hesitated.

A chaplain was in the room and said, “I’m so glad you could be there for this vigil.”

Scanning my brain for the definition of “vigil”, I stepped into the shadowed room, alone with Ruth. Sorry for her being there alone, yet glad for myself to have gotten there.

I rested in the silence; studying her silhouette, remembering my mom saying her breathing had been so shallow that morning that she surely wouldn’t live. I sand softly a few of the hymns that I knew she liked, barely able to perceive movement, holding my own breath to see if her chest was rising.

My cellphone shattered the holy hush.

Startled and embarrassed, I answered as quietly as I could. My mom said they were at Pizza Hut and wondered if I’d come.

When I said I was with Ruth, she inquired in a not-so-subtle tone, “Are you gonna stay there till’ she dies?!”

I felt heat rise in my face. As my eyes adjusted to the dark, it was dawning on me, maybe she was already dead – but wasn’t that movement I’d seen?

I got off the phone with my mom and touched Ruth’s skin. It felt like cold clay.

The movement had been rigormortus.

She was gone. I was the only one there.

I felt so much like an adult and so much like a child all at the same time.

Meanwhile, back at the Pizza Hut, my mom and company announced to the waitress who had just taken their order, “We’ve got to go – our aunt is dying!”

Five minutes later, after receiving my announcement that she’d died, they shuffled back into their booth, telling the baffled waitress, “We’ll each have the buffet – our aunt already died.”

Carbs are a big part of the grieving process in places like rural Indiana.

I can’t make this sort of stuff up. It made me laugh in the midst of the sadness. I knew Ruth would have laughed, too.

My dad had to borrow Danny’s pants for her funeral, since he came to town without khakis. I gave him strict instructions not to spill on them, knowing Danny would be needing them for his own burial very soon, even if the bottom half of his casket was going to be closed.

We barely got through Ruth’s funeral. When I returned to Danny’s side, he was suffering from repeated seizures. My mom described them by saying, “They were like his own personal earthquakes”.

Those seismic events shook me, too.

I could tell by the grimace on his face that another round was coming. It was like watching a woman in labor. At regular intervals, he would reach toward me, swallowing my hand in his massive grip. Those fingers were the only part of him that had retained strength.

He shook, and I shook, too. Even Danny’s dog couldn’t bear to watch, he’d wince and wine, burying his long nose under my arm or beneath the pillow beside me. It was just too much to take.

Two days after burying Ruth the black SUV from the same funeral home drove back the long gravel driveway to take my uncle’s body from the house he’d built with his own two hands. His pants had been returned. Ironically, we noticed a stain on his shirt just before people arrived for the Visitation. It was too late to do anything about it. His son said, “That’s okay, he was always spillin’ stuff on himself anyway,” and added that it made him look more like himself.

I Worked Through The 90-Day Novel Alone – I Don’t Think Anyone Really Knew How Close I Was to Collapsing

The weight of all those stories, and a century and a half of history from the barn, were converging upon me as I stood in the line by Danny’s casket, unsure if I should be there, since I was a niece and not a daughter. Smiling, and hugging people, and thanking them for coming, and for all they’d done for us, I tried to stay in place despite my insecurity.

His death had been beautiful.

I didn’t know it could be that way; but then, in the aftermath chaos snatched away the calm. Just after he ceased to inhale, green slime came shooting out of his mouth, pouring down his chin.

I ran for paper towels.

A nurse pulled up.

The dogs went crazy.

Phone calls were made.

People said they were sorry and then started venting to me about their own problems. In my heart I was pleading with them to stop, to let me go back to him; but pretended to listen, afraid to appear impolite.

I just couldn’t bear any more weight and wanted those moments protected. There were too many sad stories pressing into my soul. I couldn’t bear the weight of more. I didn’t want to carry anybody else’s grief. I simply couldn’t. I’d sought comfort in picking up the phone; but only finding more suffering on the other end of the line made me want to flee, even from friends.

The picture in my head of the green slime that had drowned Danny kept replaying.

I’d been hearing the gurgling slurp for days, as fluid filled his lungs, like rising water in a well.

Maybe I shouldn’t have said that about the slime; but somehow I needed to.

It was so unexpected. At night, when I would try to close my eyes, that’s what I saw.

I Needed Rest; But I Really Needed to Write – I Had To Have an Outlet for All That Pain that Was Preventing Sleep

During the seven months while I cared for Danny, people kept telling me with concern that I needed to take a break; but I couldn’t. I needed to finish the race with him. To leave felt like a form of abandonment. When I witnessed him cross over from this world to the other, I knew it was finally time to rest; but I still couldn’t, because I kept reliving all those scenes of suffering.

Besides that, those same people who had said to me so many times, “You need to rest!” immediately began inquiring in the line toward the casket, “Now what are you going to do?”

I didn’t think I could do anything. I just wanted to go to bed and listen to sad songs on YouTube, as if those would draw out my pain and somehow distill it.

There were other factors which I still can’t bring myself to say. Even today, I’m continually working through aspects of the ever-expanding story, one manuscript at a time.

In My Grief, I Decided to Write; but Wasn’t Sure Where to Start

I felt pressure to suddenly jump back into normal life; but I knew I was out of strength. Besides, it was so rare to be facing a season where no one needed me. I’d been wanting to write books for years; but other things always stood in the way.

When Jean died, a month and a half before Danny, her granddaughter and I were talking about the barn being rebuilt. I remember her saying distinctly, “That barn is like a full-circle story!”

Those words kept boring deeper into me core, like an unending auger, refusing to rest, until I’d surrender and write what was digging into my body and brain.

There was something about the story insisting it be recorded.

Jean’s grandparents had lived on that farm long before mine had bought it. Her granddad needed help and hired a young man who fell in love with the farmer’s daughter. That’s how Jean came to be. She remembered sitting out in that barnyard, watching her mother watch the front half of the house burn. Jean must have been about nine then.

She was a comfort to her mother that day, and she was also a comfort to me – both when my family sold the farm, and as it was being taken down. I remember walking through the house while the new owners remodeled it. They’d pulled off the plaster, exposing bricks that were mysteriously blackened. Jean was the link to the past. She had witnessed the flames. Peeled paint was on a set of neglected doors in the attic, melted by heat from the fire, preserved as a reminder that life had returned to that home even after all seemed lost.

That story of Jean’s mother’s tears was like a phoenix to me, forming a connection between us that brought me great comfort. It added to the contents of the accounts about Wabash, which I thought ought to be told by somebody.

I realized that somebody should be me; but I was afraid.

I’d tried and failed at book writing before. I needed some sort of direction.

To Me, Buying The 90-Day Novel Was One of the Scariest Investments I’d Ever Made

Wondering if I could write, fearing another false start, I happened to see an interview on YouTube done by Jennifer L. Scott of “The Daily Connoisseur” encouraging people to read The 90-Day Novel and work their way through it. She had participated in Al Watt’s L.A. Writers’ Lab and had a very positive experience.

I just wasn’t sure.

I didn’t even own a computer.

I hadn’t earned an income in the seven months I’d been taking care of my uncle.

I had little money and even less confidence.

It wasn’t just the cost of the book and technology that made me afraid. It was the risk of another failure. It felt safer to stay on the ground than it did to try and stand.

Hope deferred makes the heart sick, and I’d had mine put off for far too long.

God used the process of working through those daily lessons to begin to renew me.

The interview with Al Watt made me wonder if I should try.

The story of Wabash was demanding to be told.

Memories of what I wanted shared, even before Danny got sick, were flooding in.

Thoughts of my grandma, so stiff and busy, and how she’d softened as she slowed down and became a centenarian; letting her dry humor come out in funny quips during those long days at the nursing home, with statements like, “They pay me to work here. I don’t really do anything; but that’s their problem, not mine.”

I remembered how much her care had cost, and how there had been talk back then about the possibility of needing to sell the farm to cover her expenses; but how the trees my grandpa, Woody, had planted could be cut. He’d put those saplings in the ground years before, knowing he wouldn’t live to see them harvested.

Old men don’t plant trees for money.

They put seedlings in the ground for the sake of love.

I remember walking in the woods one day and seeing mature trunks marked by pink paint – a sign that they would be culled by loggers soon. Something about it made me smile, reminding me of lovers carving their initials onto trees. That pink paint seemed to declare “Woody loves Libby” on every marked tree. He was still seeing to her provision, having had the foresight to plant that forest.

I thought back to a poem I’d seen after my grandma’s death, which I was surprised she’d written, entitled, “A Walk to the Woods”:

“A Walk to The Woods”

It was early March

But the day was warm and fair

So, we walked together to the woods

And looked at trees Woody had planted there,

Thru the thicket, over the hills,

Stood walnut, white pine and oak

Beautiful blue spruce, too,

It was as if they really spoke.

Tho the underbrush was thick,

A little hard for walking,

It was evident, the way he admired each tree,

There was no need for talking.

He is so very much in love,

But I’m sure it’s not just me –

It’s every hill and dale

And every beautiful tree.

Elizabeth H. Miller

Reading those words made me want to tell the story of their love for each other. I wondered, after I met Jean, if her grandparents had walked back to those same woods when they lived there, and imagined her mom and dad probably followed the same path, down the dusty lane I’d loved all my life.

There were so many layers to the story.

Unwritten words overwhelmed me,

washing through my mind like a torrential rain,

refusing to be ignored.

Everywhere I turned, I came across more clues and connections.

Al Watt’s Instruction on Story Structure and Outlining Was What I Needed to Organize My Writing

I had so many scraps and fragments of thoughts when I first started; but Al Watt’s book helped me bring them together. In less than 90-days, I realized I didn’t just have the makings of a book; but material fit for a series, thanks to his explanation of “The World of the Story”.

I knew instantly what the world of my story was.

It was Wabash, Indiana.

I couldn’t get the words out fast enough. Before I got the courage to buy a cheap tablet with a keyboard attached, I borrowed my uncle’s computer, typing my words in emails to myself, since I had no other means of saving them.

It’s a wonder I didn’t electrocute myself, sobbing and sniffling over the keyboard.

“Sniffling” isn’t a very descriptive word of what was going on; but I don’t want to be gross. I was ugly crying for a lot of the time that I typed; but I’m so glad now to look back and see the resiliency which that painful process produced in me.

A great deal more suffering has come since; but having the discipline to record it, thanks to Al’s encouragement to write daily, has helped a great deal.

That was probably far more detail than I needed to include for a book review on The 90-Day Novel; but I felt like I needed to go beyond saying, “five stars” and express how this book took my habit of “journaling my life away” and helped me see some purpose in the painful process of surrender.

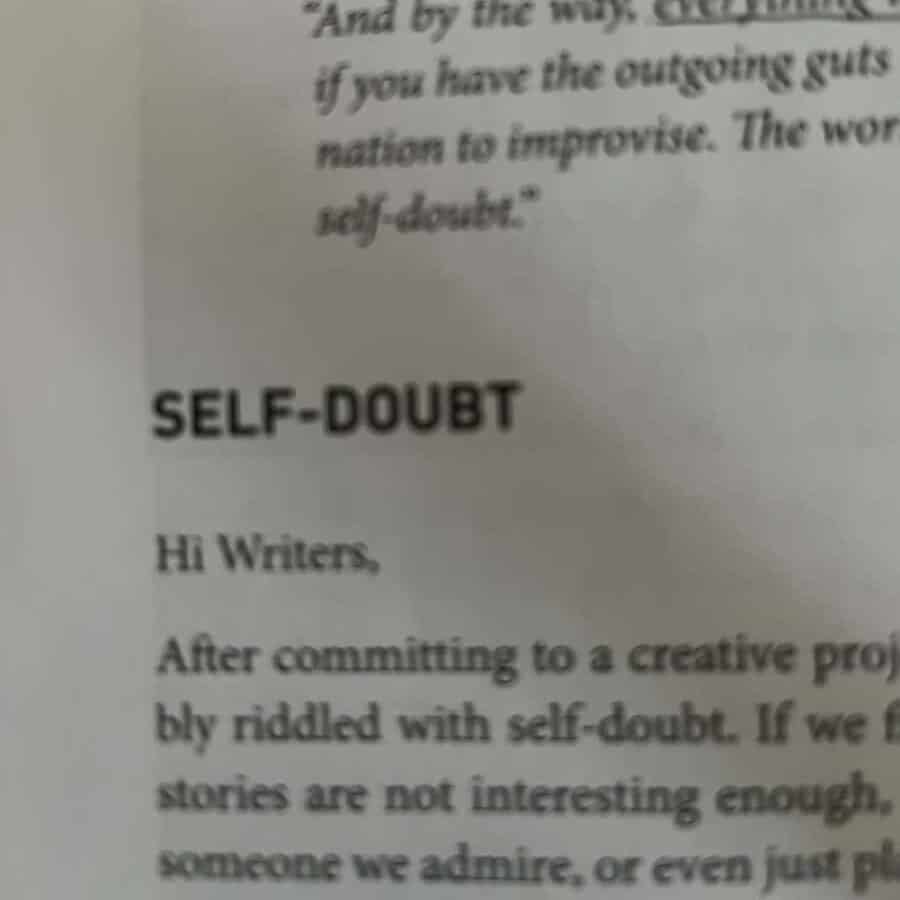

Anytime someone sits down to write a story, they are also contending with the real life story they are living through. Al Watt does a great job of acknowledging that, offering words of armor to wanna-be-authors as they battle through the war of self-doubt in their brains.

Book Review of The 90-Day Novel by Alan Watt

I did write a much more succinct review earlier; but somehow the link keeps sending me to a “404 Error” page. I still have so much to learn about building a website; but instead of getting discouraged, I’m determined to keep slogging my way through, realizing I’m not the only one slow to learn.

Al’s book made me feel less alone in the struggle.

Besides, he says we need to give ourselves

permission to right poorly.

(I’m laughing, because I just went back to edit this and saw that classic typo – I’m just gonna leave it for now… I’ll give you a hint as to why – Al’s got another book about that called, “The 90-Day Rewrite”. Maybe someday I’ll review that one, too.

How Will Reading The 90-Day Novel Help to Improve Your Writing?

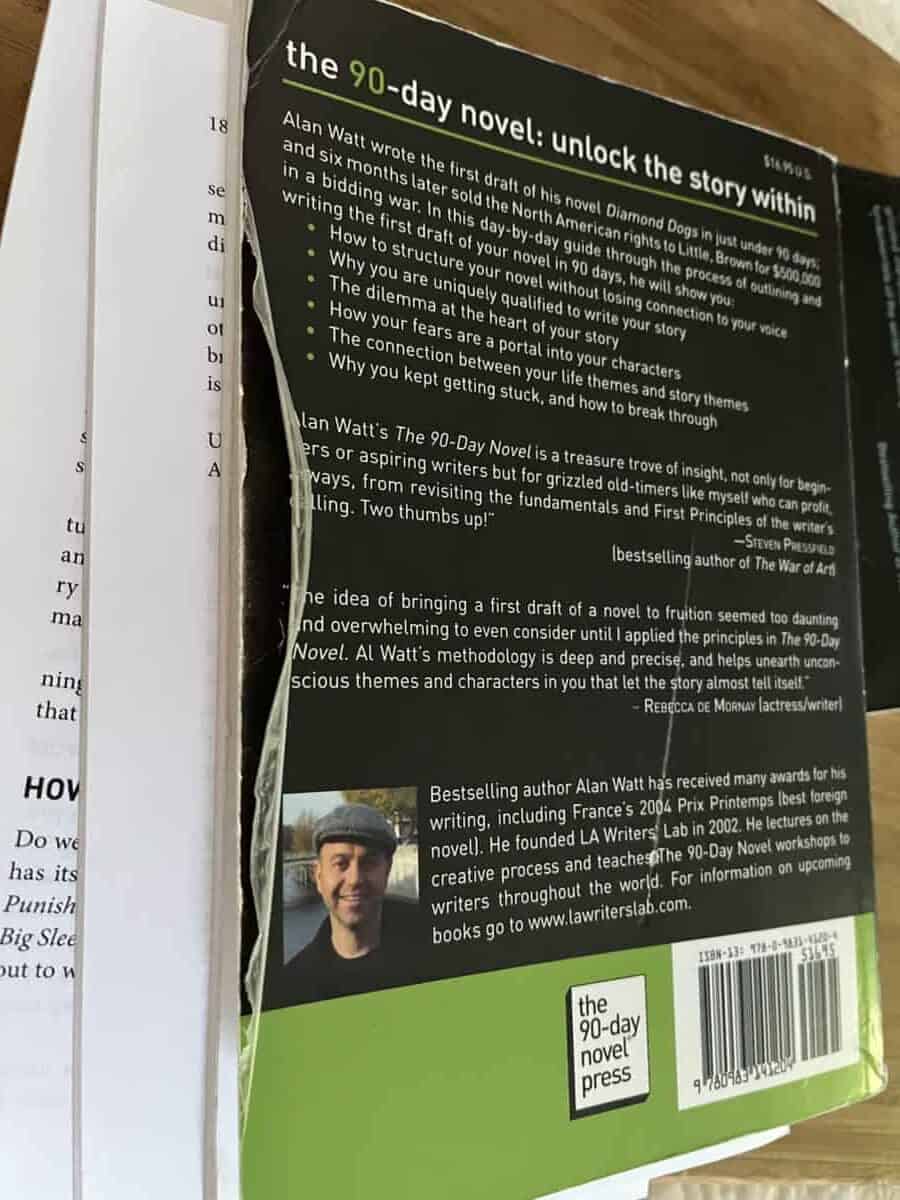

Watt offers a straight forward, practical approach for outlining a novel, explaining the arc of story-telling – from an opening line, on through the climax, toward a redemptive end.

His explanation of learning to shift perspective, instead of getting stuck trying to fix unresolvable problems, isn’t just helpful for writing – it’s good advice for life.

The book is comprised of ninety daily letters with helpful instructions, which both push toward the goal of completing a novel in ninety-days, and pat the writer on the back, to prevent total discouragement during this daunting task.

The 90-Day Novel didn’t just help me write a novel. God used it to help me work through a lot of pain and start piecing my life back together in the midst of deep brokenness. It gave me a gameplan for gathering all those story fragments and organizing them into something that made more sense.

Even if my story is never read by another soul, I know that I needed to write it for myself.

If you only buy one book about writing, I would make it The 90-Day Novel.

Sincerely,

Jody

If you’re struggling to wade through the process of readying your story for publication, you might find some encouragement from this post, where I share some of my personal struggle with sitting down at the computer: Corpses, Plastic Bottles, Glitter, and the Baby Moses – What Hope Has to Do with Saving Your Story as a Writer

Recent Posts

I'm doing some behind the scenes work for a few weeks, so I'm keeping these posts a bit more broad and maybe even a little vague for a season. I'll explain more later. What Did I Accomplish...

What is Alt Text for Images and Why You Should Use it in 2024

When I started this website and began uploading images to my posts, I was told, "Don't worry about that box that says "Alt Text for Image", it doesn't matter; but I have since learned that it does...