This post may contain affiliate links.

Episode One in the Saga of The Cruise that Left a Bruise – The Backstory…

I believe it was March 18th of last year that my dad told me he planned to take a trip around the world.

I had no idea how that little announcement would send me on a trip as well.

We were in the living room. My parents and I.

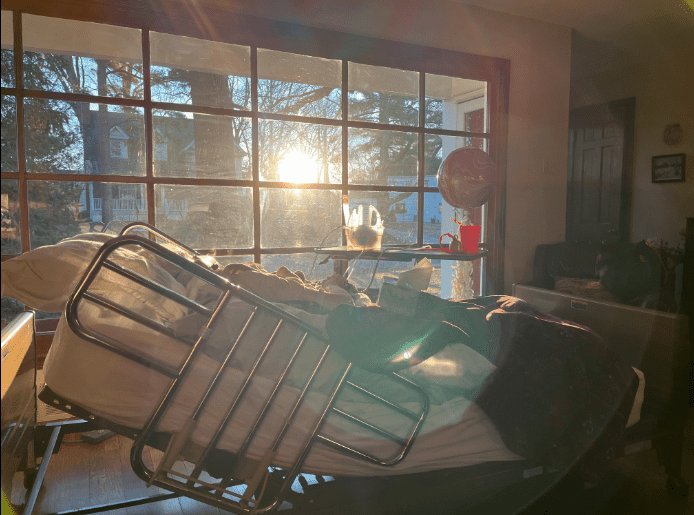

My mom was in her hospital bed, which sat in the middle of the floor, parallel to the picture window, with her view of the world.

Cardinals, squirrels, pedestrians, dogs, cars passing by, and the occasional chipmunk.

Tulips and hyacinths, tipping down in death, were making way for peonies, knock-out roses, and hydrangeas to put their petals on display.

I was standing on the hardwood, between her and the couch.

She was dying.

She’d been dying for a long time.

Pancreatic cancer and dementia. Or was it chemo brain? Or “covid brain” as she tended to call it.

She’d been on Hospice more than a year.

She’d signed up the day following a bad reaction to high-beam radiation.

The doctor had told her he had no doubt she should follow his recommended treatments.

One hundred percent, she should participate in his study.

He read off the extensive list of possible side-effects, which included death and paralysis, then felt his pockets for a pen, so she could sign.

He couldn’t find one, so he stood to excuse himself, saying he’d go get something to write with.

I felt a rush of relief, wanting desperately to speak to my parents in private. Something about his demeanor made me feel like she was signing up for a time share – one that our family could never walk away from.

It scared me; but I didn’t want to stand in her way, if radiation would help with her cancer. I didn’t want to be misunderstood and seen as somebody who only relied on natural remedies.

I knew radiation wouldn’t be a cure, nor would the “cure-all” at the other end of the spectrum: Apple Cider Vinegar.

Not for pancreatic cancer.

Not at this point.

When she’d first been diagnosed, my mom had sighed and said, “Well, that’s a death sentence.” As a nurse, she knew it wasn’t good.

Some may survive for a while; but at her age, in her current state of health, it was highly unlikely. Besides, she didn’t know that she had the will to live – by that point, she felt so tired, all she wanted to do was “crawl in a casket and sleep forever”.

But then they’d done that stent, and she’d gotten better.

A few days later, it got bad again.

Another trip to the hospital and a stent in another spot, and she was better again.

Then came chemo.

It felt like fireworks were going off in her feet from the pain of neuropathy.

Her hair fell out.

She got scabs all over her head.

Her eyeball started bleeding.

I didn’t know where to set my own eyes when I saw her. It was painful to look and painful to look away. My first instinct was to exclaim to myself, “They’re killing her.”

She could barely shuffle, making her way across the back deck in that light blue bathrobe she loved to wear.

Then she could hardly move from bed.

The next step was prehab to prepare for The Whipple Surgery – which would be to remove and rearrange all sorts of organs.

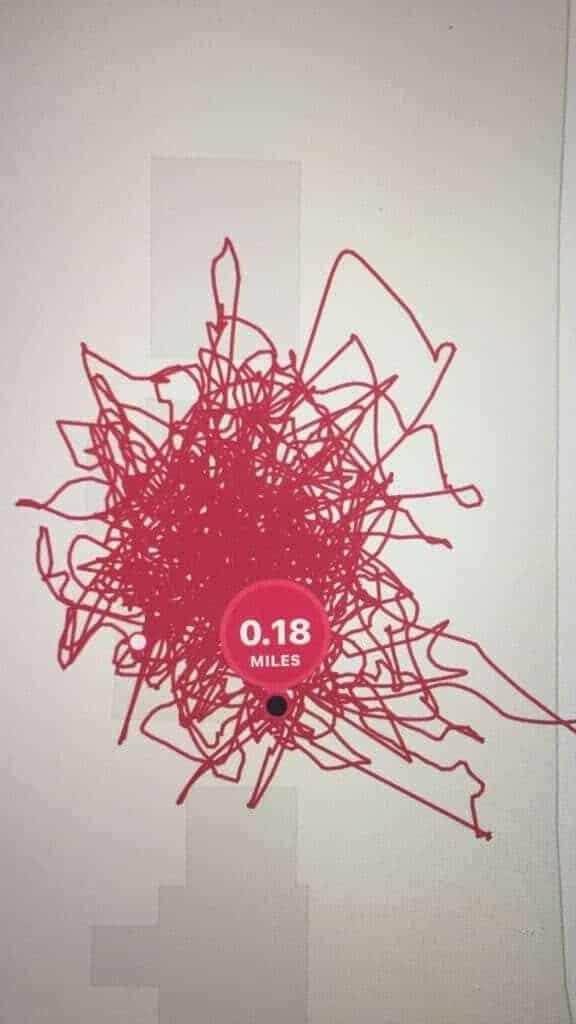

She wore a Fit Bit. The GPS tracking looked like something her granddaughter might have scribbled.

She could hardly walk; but insisted on trying, pushing her wheelchair.

She didn’t qualify for surgery. She was disappointed and relieved.

The radiation doctor felt one last pocket and realized he’d had a pen all along. He wasted no time in thrusting the clipboard into my mother’s hands and pointing to where she should one-hundred percent, no doubt put her signature.

I did not speak.

High Beam Radiation was the next part of the treatment protocol. She’d been sent down the disassembly line of doctors – this was all part of the process.

My mom had to give up Cheerios, because the iron in them would show up like lots of little dark, unchewed rings on the imaging. I’d hardly heard her complain before then; but a break in her breakfast tradition became a hardship worth speaking up about.

Beth’s Cheerios

A handful of frozen blueberries from the freezer drawer she was too weak to open.

“Did you rinse those off first?” she’d want to know. She didn’t like the kind that came frozen. She wanted fresh ones, stuck in the freezer. The box would get bumped and there would be stray blueberries all over the bottom of the disorderly appliance. I’d sigh and try to gather them back together, then follow the rest of her instructions: a few pecans, but not too many, because “they’re fattening and expensive”.

I’d remind her that her doctor wanted her to gain weight; and she’d say, “Oh yeah,” but the mantra, ‘I shouldn’t be eating this’ had become such a habit, she couldn’t help but keep using the phrase, even as her frame continued to shrink. Her kneecaps seemed to bulge; but it was just that the rest of her legs were wasting away.

Milk came on top of the pecans, then one spoonful of white sugar on the very top – otherwise it was in danger of being dissipated by the milk – and a certain kind of spoon, with a wide handle, because her hands shook, and she couldn’t hold the other ones.

She did that first round of high beam radiation in February of 2022, then wanted a Rice Krispy Treat in the Starbucks at the hospital. She was so happy to think of eating it; but as she turned to go, something went dreadfully wrong inside her, and she threw up in the paper sack right there in the restaurant.

The brown bag with the green lady completely came apart with that unexpected force of saturation.

I won’t go into details, other than to say, the crowd parted, someone went for a mop and a Wet Floor sign, and all my mom could say was that she still wanted that Rice Krispy Treat.

Yes, she’d thrown up on it and was standing there with vomit streaming down her purple fleece pants; but the Rice Krispy Treat was still in its wrapper, so it hadn’t gotten wet – why couldn’t she have it?

She got home and got into bed and was still talking about that disappointment of her confiscated dessert into the evening, when the side effects of her treatment started growing worse.

It was her spine. It wasn’t her pancreas. It was her spine.

I remembered the doctor reading off the list of possible side-effects and how my mind had frozen on “paralysis”.

It was the middle of the night. I’d moved her from the bedroom to the living room, thinking she might be more comfortable.

She was sitting on the couch, because she couldn’t stand to lie down. I was on a child sized mattress on the floor, trying to use an ottoman for my feet, because I was so tired, I couldn’t stand to sit up any longer, but knew I couldn’t leave her alone in that condition.

She said the pain was at a ten.

I could hear the pelting of the sleet outside.

I said, “You’re a nurse. What would you tell someone to do, if they were in your situation?”

“I’d say, ‘Go to the ER’.”

Another truck went by in the blackness out front, scraping the ice, scattering salt.

“Well, do you want me to take you?”

“No. I don’t want to go anywhe – OH! My SPINE! My SPINE – it’s killing me!”

I tried to get ahold of the doctor. The one who had handed her that pen and watched so carefully while she signed her name.

I hadn’t liked him.

She hadn’t either.

I don’t think he liked her.

She’d offended him by asking for his credentials.

He’d blinked. Hadn’t she read the signs in the lobby? The ones saying that he was the head of the department? He thought that response should satisfy her.

This display of his bedside manner made us even more skeptical.

I don’t think he liked me either.

I’d asked what he would do if this was his mom or dad.

He’d said, “I’d tell them to do it. One hundred percent I’d tell them, ‘Do High Beam Radiation’. No doubt.”

I didn’t like that answer. ‘One hundred percent?’

Dr. Sanford, across the hall, the one that would have been my mom’s surgeon, if she’d done The Whipple had said, “If it was my mom, she’d do surgery, no doubt – but if it was my dad, there’d be no chance he’d want to go through The Whipple. Everybody’s different. Each patient has to decide for themself.”

I liked that answer.

My mom liked Dr. Sanford. Despite her lack of energy, she’d gushed, “He’s so down to earth, and so cute, and so nice. I just bet he played baseball. He’s the kind of guy who played baseball. You can tell, because he’s so laid back. I’m almost disappointed not to do The Whipple, because I’d like to see him again.”

Sure enough, we soon bumped into somebody we knew who said, “Sanford? That sounds familiar. Oh yeah, I think I played baseball with him in high school.”

My mom was triumphant. “You see?! I said that! I just knew. I’d said from the beginning, ‘Dave, I bet he plays baseball. He’s just so down to earth.’”

My mom had been right about Dr. Sanford, and I think we’d both been right about the other guy, too. When I finally got ahold of her radiation doctor to tell him what had happened (with the Rice Krispy Treat and the spinal pain), he tried to convince me her condition had nothing to do with her radiation treatment, even though her symptoms were the same things he’d read from his long list of possible side-effects.

Within a day or two, my mom picked up a pen again, and signed her name at the bottom of some Hospice papers. She was opting out of further treatment, seeking only the kind of care that would keep her comfortable until the end.

Thirteen months later, she was still with us.

I had people tell me that she wouldn’t still be alive, if I wasn’t taking such good care of her.

I had no idea how to respond to that.

What did that mean?

Was it a compliment, or were they insinuating I was doing too much?

Someone had commented, “Your hair has gotten significantly grayer. You’ve sure had a lot on your shoulders.”

I knew that. I also knew my eyes were getting worse. My heart was skipping beats. Sometimes I was so exhausted that I was scared to stand up. But I did. Up and down. Up and down. All night. From the mattress on the floor beside her hospital bed, there in the living room, between her and the picture window, with lights shining in, trying to convince my parents to please let me put up curtains.

They resisted. They liked the room with no curtains. They’d had drapes before. Decades before. Forty-eight years in that house. They didn’t want to move, and they didn’t want to change a thing.

But how was I supposed to change my mother right there in front of the living room window? Multiple times day and night. My stress level was through the roof.

My life felt like a show. That living room a stage.

The audience: the neighbors walking by, and people passing in their cars, possibly the creepy guy down the street, who some said had a habit of pointing a telescope towards people’s windows. There were folks unexpectedly walking up the driveway or waving on the front porch just a few feet from me in my makeshift bed, if I hadn’t yet stowed it away for the day.

Now you know the setting, and a little bit of the background experience I had with having a parent sign up for something.

There we were in that same living room – the one my dad had said in December that he would never sell, beside my mom’s hospital bed. I’d say he had been in a pretty deep depression – taking multiple naps throughout the day; but there was a new glint in his eye.

He said he had an announcement to make.

“I’m signing up for a three-year cruise. It’ll be a trip around the world. I’m going to completely downsize and sell this place. The ship leaves from Turkey in November.”

I hadn’t seen that coming.

It was March. Surely my mom would be gone by then.

I wondered what would happen next…

Stay tuned for the next episode in the saga of The Three Year Cruise that Left a Bruise:

For more about my mom’s affection for Cheerios as part of her breakfast routine, please read below:

Recent Posts

This day marks the stopping point for me trying to "get my stuff in order" for a while. I've been building a foundation for having my ducks in a row so I can launch into a visionary season,...

Thursday night I went to listen to Anne Lamott. I wasn’t sure about going. Some of her writing I like; but some makes me squirm. I think I like how she’s real; but worry she’d reject...